Christian-History.org does not receive any personally identifiable information from the search bar below.

Medieval Christianity 1:

The Early Middle Ages

We leave the post-Nicene era and enter medieval Christianity with a vastly different Church than that which existed before Nicea.

Ad:

Our books consistently maintain 4-star and better ratings despite the occasional 1- and 2-star ratings from people angry because we have no respect for sacred cows.

The independent churches that could boast of a unity produced only by faithful maintenance of apostolic doctrine and a common obedience to Christ had given way to a vast hierarchy ruled by local bishops with great prestige and some political power. Those bishops were answerable to even higher bishops, metropolitans over cities and 4 patriarchs ruling the entire Roman empire.

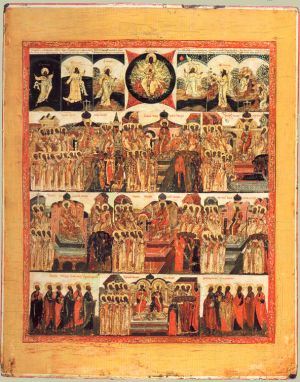

Depiction of the ecumenical councils

Depiction of the ecumenical councilsThe unity of medieval Christianity was based on doctrines determined to be important by councils. Those councils were called by bishops and emperors and were both local, national, and empire-wide.

The local ones often disagreed with each other, and occasionally were called purposely to disagree with one another. It was the nature of the time.

Politics and the Roman Empire

After Chalcedon, things were not so simple. In 476, the last emperor in the west was deposed by the German chieftain Odoacer. Until Charlemagne was crowned king of the Franks in 800, the former western empire was ruled by a series of Germanic kingdoms.

The eastern Roman empire would continue under the rule of Constantinople until 1453, though they suffered heavy losses to the Muslims beginning in 622.

The Muslims conquered virtually all of the Middle East between 622 and 640, including the important cities of Jerusalem and Antioch, then swept through north Africa from 642 to 695, almost eliminating Christianity from the area. In the early 8th century, they pressed into Spain before being stopped by the Franks in 732.

They also conquered all of Persia, where they would become known as the Turks and be a thorn in the side of the eastern Roman empire until they finally overthrew Constantinople in 1453.

Thus, the political situation was a lot more complicated in early medieval Christianity than during the ante-Nicene and post-Nicene eras.

During all of medieval Christianity, people held to the religion of their leaders. As the German tribes conquered first parts and then all of the western Roman empire, they were converted to Christianity—not to the free, wholehearted discipleship of the apostles, but to the national religion that medieval Christianity had become. As a result, despite the conquests, Europe remained a "Christian" continent during the Middle Ages.

Interestingly enough, some of the Germanic kingdoms were Arian! They disagreed with the Nicene council and held to Arius' belief that the Son was created from nothing like all other creatures.

The crowning of Charlemagne by the pope in A.D. 800 would put an end to those sorts of deviations of the Christianity of the councils.

Who Was the First Pope?

Justo Gonzalez writes this about the title of pope:

The title of "pope" has undergone a long evolution, and therefore it is impossible to say exactly who was the first "pope." (The word "papa" was a term both of endearment and respect, and in earlier times was applied to any bishop who deserved particular respect, such as Cyprian in Carthage or Athanasius in Alexandria. When the bishops of Rome began receiving that title, it was still being used for other bishops.) (Church History: An Essential Guide, p. 43, parentheses in original)

It is clear from letters written in the 5th century and later that the bishop of Rome was gaining a primary prestige in early medieval Christianity. Even Protestant scholars are usually willing to call Gregory the Great (590-604) pope, but it's possible it could be legitimately applied to bishops as early as Leo the Great, who was bishop of Rome during the Council of Chalcedon.

Linus, a bishop of Rome, is supposed (incorrectly) by Roman Catholics to have been the 2nd pope.

Linus, a bishop of Rome, is supposed (incorrectly) by Roman Catholics to have been the 2nd pope.The other patriarchs—those bishops given authority over whole regions at the Council of Nicea (see Post-Nicene era)—were willing to acknowledge that the Roman bishop was the primary leader of the patriarchs, but they saw him as a first among equals, not a ruler by himself.

Later, this would directly lead to the Great Schism, which divided the western half of the church from the eastern, leaving only the Roman patriarch—the pope—in the west, while the other patriarchs became leaders of the modern day Orthodox Churches.

The conquering of the western empire by the Germanic tribes led directly to the isolation of the Roman bishop. He had a lot to deal with keeping medieval Christianity alive and orthodox under barbarian rule. This did not allow a lot of focus on working out doctrinal issues with eastern patriarchs, and the Roman bishop learned to work alone.

When Charlemagne proved an able enough leader to unite much of Europe, it was a great relief to Rome when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as emperor of the revived Holy Roman Empire. This provided some stability, gave the pope political clout, and allowed renewed interaction with the eastern patriarchs, though this interaction did not go well.

Monasticism in Medieval Christianity

The monks, having gained the respect of everyone, proved a great boon to civilization. Whatever we Protestants may think of their religion, it is the monks who preserved Christian learning for us and who can be given much credit that we have a Bible that is as reliable as it is.

Much of the ancient culture disappeared, and the only institution that preserved some of it was the church. For that reason, even in the midst of chaos, the church became ever stronger and more influential, with monasticism and the papacy playing important roles in the process. (Church History: An Essential Guide, p. 43)

The most important monk of early medieval Christianity was St. Benedict. In 529 he wrote a rule for his monastery that would become the rule for almost all monasteries of early medieval Christianity. It emphasized physical labor and involved vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

The Benedictine Order of monks survives to this day. Monasteries were indeed the centers of learning in the Medieval period.

Feudalism

Since Christianity had become a national religion, where citizens held to the religion of their leaders, feudalism becomes an important issue in medieval times.

Feudalism is a system where all land is owned by nobles, and the citizens worked the land for the nobles. This created many more political leaders, which will prove crucially important when we leave Medieval Christianity to address the Reformation.

Feudalism arose as Europe suffered turmoil under German rulers and was squeezed in by the Muslims. Trade declined, and the only thing of lasting value was land. Those who owned the land became the rulers of the people.

The exception to this was the cities, which did not do well in the early medieval period in Europe. Cities thrive on businesses, crafts, and money, and these are only in plenty when trade with other countries is doing well. It was not.

The driving out of the Muslims and a growing hunger for learning in the late Middle Ages would restore trade and cause cities and educations to thrive, but that is for the next section. We can end our section on early medieval Christian with a description of the Great Schism.

The Great Schism

With some semblance of political peace achieved under Charlemagne, Rome was able to turn its eyes outward.

As the meager interaction between Rome and Constantinople increased, one particular issue came to the forefront. The Nicene Creed, as it was approved at Constantinople in 381, had been changed in the west.

It had not been changed very much. In Latin, it was but one word: filioque. But what a big word that would prove to be!

Filioque means "and the son." The Creed, as confirmed at Constantinople, said, "We believe in the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from the Father." Rome had added "and the Son" to the end of that line, making the Holy Spirit to proceed from both other divine persons.

Though the patriarch of Constantinople had no doctrinal problems with the addition, he insisted that the Roman patriarch, the pope, had no authority to make changes to the official creed. As a first among equals, such a change could only be made at a council with the approval of all the other patriarchs.

The Roman patriarch, who by now saw himself as the lone heir to the keys of the kingdom that Christ gave to Peter, insisted that he did have such authority.

This debate flared up in the 9th century, then sat on the back burner until an emissary of pope Leo IX excommunicated the patriarch Cerularius of Constantinople in 1054. This is known as the Great Schism, and it has split catholic Christianity in half for almost a millennium.

The churches affiliated with the patriarch of Constantinople, and even those excommunicated at Ephesus in 431 and Chalcedon in 451, are known to this day as Orthodox Churches, and those affiliated with Rome as the Roman Catholic Church.

It is of note that Pope John Paul II once said the Apostles Creed publicly without the filioque.

Early Church History Newsletter

You will be notified of new articles, and I send teachings based on the pre-Nicene fathers intermittently.

When you sign up for my newsletter, your email address will not be shared. We will only use it to send you the newsletter.